- Home

- Ivana Bodrozic

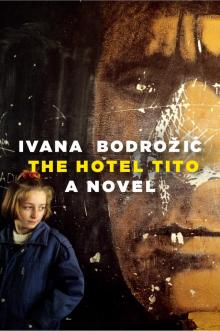

The Hotel Tito

The Hotel Tito Read online

THE HOTEL TITO

IVANA BODROŽIC

a novel

translated by

ELLEN ELIAS-BURSAC

seven stories press

new york • oakland

Copyright © 2010 by Ivana Bodrožić

English translation © 2017 by Ellen Elias-Bursać

First English-language edition November 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Seven Stories Press

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

sevenstories.com

College professors and high school and middle school teachers may order free examination copies of Seven Stories Press books. To order, visit www.sevenstories.com, or fax request on school letterhead to (212) 226-1411.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Simić Bodrožić, Ivana, 1982author. | Elias-Bursaâc, Ellen, translator.

Title: The Hotel Tito : a novel / Ivana Bodrozic ; translated by Ellen Elias-Bursac.

Other titles: Hotel Zagorje. English

Description: First English language edition. | New York : Seven Stories Press, 2017. | Translated into English from Croatian.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017031180| ISBN 9781609807955 (hardback) | ISBN 9781609807982 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Women authors, Croatian--Fiction. | Yugoslav War, 1991-1995--Croatia--Fiction. | War victims--Croatia--Fiction. | BISAC:

FICTION / Coming of Age. | FICTION / War & Military. | HISTORY / Europe / Eastern. | GSAFD: Autobiographical fiction. | War stories.

Classification: LCC pg1620.29.i44 h6813 2017 | ddc 891.8/236--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017031180

CONTENTS

The Hotel Tito

Afterword

References

THE HOTEL TITO

I don’t remember much of how it all began. I remember flashes: windows flung wide in our apartment, a stuffy summer afternoon, manic frogs from the Vuka. I wriggle between two armchairs and hum—Whoever claims Serbia is small is lying—Papa folds the paper and turns to me, I feel his irritation. “What’s that you’re singing?” he asks. “Oh, nothing, a song from Bora and Danijel.” “Well stop it!” “You bet, ćale.” “Don’t call me ćale, I’m your papa, and damn him to hell!” I don’t know why my papa’s grumpy about the song or who he is, but I have a sneaking feeling it has to do with politics because everybody talks about politics all the time.

We’re packing to go to the coast. For the first time ever my brother and I are going on our own. He’s sixteen, I’m nine. Our neighbor Željka, a year younger than my brother, she’s going too. I want to be exactly like her and I’m so thrilled because my mother and hers asked her to look after me. I don’t sleep a wink all night. On the table between my brother’s bed and mine are our passports. The light’s been switched off and I ask my brother, can I come over to his bed? “Why passports if we’re only going to the seashore?” I whisper. “Papa says if things heat up we’ll go stay with Uncle in Germany,” he says. I don’t get the part about things heating but maybe this has to do with politics, too. I know a thing or two about politics myself, like I call my toy monkey Meso, because my monkey and our president look a lot alike. My brother and I try to imagine Uncle’s life in Germany. He says everybody there is so rich that apartments like ours would be for gypsies. I adore my uncle. He comes every summer, he has a young wife who’s German, people listen when he says something and he smells super nice. This summer his wife brought along a little poodle, Gina, and Granny and Grandpa wouldn’t have it in the house and they said it had to sleep in the shed. There was a huge fight, Granny said she’d poison the fleabag and Papa went to calm them down. Gina stayed in the house. Uncle brought us presents and marzipan, as always. I got a leather volleyball that couldn’t be inflated. My brother got a soccer ball, but he never used it. Soon my brother chases me back to my bed and I spend hours that night thinking about everything.

The bus station in Vukovar smells, it’s early in the morning, I’m sleepy and I’d rather be in bed. Papa’s carrying me, even though I’m big, he carries me the whole way. He’s wearing white pants and a blue T-shirt. We pull apart and kiss, first we make silly faces and then we air-kiss. It’s our thing. There are lots of kids at the station and my brother and I take seats on one of the four buses. Our parents wave and wave, we wave, I can’t see mine anymore but I wave to others I don’t know and they wave back. They smile and call to us to take care, some kids’ mothers cry. Some of them run after the bus to the corner.

I’ve never been on an island before. We’ve been traveling so long I already threw up twice, and I’m not the only one. We even saw the sea a few times from the bus and then it went away behind a mountain. I’m sorry we won’t have time to swim today, but I’m a little scared, too. We swim a lot at the Štrand beach by the river, but it’s shallow there till you go very far out so knowing how to swim doesn’t matter much. I only went to the Danube with my nana who said she swam like a stone, and while I watched the other kids in their inner tubes she only let me get my feet wet and splash my face.

When we finally arrived, I was put in a big room to share with twelve other girls my age. I’d already settled onto one of the beds when Željka came in with the head lady and said we couldn’t be separated. That’s how I ended up in a room with the big girls. I was happy and nervous. Some of them were grumpy about me being stuck in their room because they thought I’d probably spy on them and snitch to the head lady, but we all became friends pretty quick. I didn’t talk much or bug them and I was polite to everybody. They called me “kid,” and I was mesmerized by their spaghetti straps, deodorants, eyeliners, Tajči hairdos. Every evening out on the terrace at the resort we called Villa Drafty we had a disco. I kept being followed around by a boy, everybody said I should dance with him because he was the son of a famous actress. During the day we played Parcheesi and splashed around in the water. One afternoon my brother asked me to take a walk with him along the waterfront and when we got to the end of the pier he shoved me into the sea. I flailed around with my arms and screamed, the water was in my mouth, and he just stood there on the pier, shouting, “Swim, swim!” I don’t know how, but soon there I was on the beach. I burst into tears, my clothes were soaked, and one of my white patent-leather shoes was gone. My brother said: “See, you’re fine.”

That’s how I started swimming.

We’re already two weeks longer at the seashore than we were supposed to be. A few days ago we were on a bus ready to leave when they brought us back. We’re unpacking our bags again. My brother stands over the sink and washes out our underpants and undershirts. Almost every day we’re served fried fish for lunch and we’re really starting to miss home. We go to the store for bologna sandwiches and yogurt. Now I’m sorry I left my newest Barbie, the one with the bendable rubber legs, at home because I was afraid someone might steal her, I only brought the plastic ones.

One morning when I went outside I saw Mama. I’ve never been so happy. She took us out for four scoops of ice cream each, and took me to a hair salon for an Italian haircut. They put her and Željka’s mother in a special room in the attic, and I slept with her that night. I listened to them talking about a person walking through cornfields, about Mira who was nine months pregnant riding a bike, and a train where all the curtains were drawn, but in bed with her was cozy. I knew she’d argued with Papa, my brother told me. He didn’t want to drive even as far as Vinkovci because somebody might think he was running away, and afterwar

d, that same somebody might point a finger at us. I asked nothing about Papa so she wouldn’t feel bad, but I did want to know when he’d be coming.

We’ve been on the seashore for a month now, the new school year is beginning and we have to go to school somewhere till we can go home.

My uncle was there when we arrived at the Zagreb train station. We drove through the city. It was gleaming in the autumn sun. Our uncle’s house was way out of town, I thought it was outside of Zagreb, but then I found out all of this is Zagreb. It’s very big. They lived in a small two-bedroom apartment on the ground level and put us up on the next floor, which was empty. I often slept in my cousin’s room, except when we fought. At first it was super nice there. Everybody treated me and my brother like we were special, and at the new school I had almost nothing to do but still got straight As. One afternoon my cousin and I were on our way back from school and when we were walking up the gravel path toward the house a siren began to wail. It was an air raid and I burst out screaming and crying. We raced into a neighbor’s house. Nothing happened but it was the start of something new. Everything got trickier in the house. Once when I wanted to go into the bathroom, my older cousin blocked my way and said: “This is my house, I go first.” The next morning while we were at breakfast, my mother’s sister said to Mama, “You’ll eat up all our bread.” At first they were always baking cakes, but then there was less to go around, and we never opened the refrigerator ourselves. Sometimes when we went to bed we heard them talking in the kitchen. Papa usually called every third day, but then eight days went by and we didn’t hear from him. On Saturday mornings we’d meet up in the main square with Željka and her mom. We’d hug and kiss like we hadn’t seen each other for ages. The two of them were staying with relatives, too, and my father and Željka’s were together back in Vukovar. We talked about what it would be like when we returned home. We went for burek or ice cream. On our way back we were quiet.

At first the people in Zagreb were better. They dressed better, they walked around on the wide streets and in the big squares, rode on the trams, without looking like they were doing anything special. They had toasters and dishwashers, there were cobwebs in the corner. That’s how we saw them. Soon we, too, were riding around on the trams for free with a special yellow ticket and getting to know city tram lines. I could ride around all day long and eat nothing but salty rolls because we were always having to visit municipal offices, the Red Cross, Caritas for food supplies, that was fun. Once at Caritas we were given a big bag of sweets and were bringing it home to our neighborhood in Črnomerec on a tram packed with people. A dressed-up lady in our car said to her friend that the refugees are the ones crowding the trams because they’re always out riding around day and night. I looked at her and smiled because I knew we were displaced persons, the ones from Bosnia were the refugees.

After two or three months of living in Zagreb some things became familiar. Autumn came and the rains started. Little by little the fun stopped. By then we’d spent nearly all the 300 Deutsch marks Mama’d brought with her. Fewer people were getting out of Vukovar and bringing us news about the old folks. That’s what we called Papa’s parents. Then one day we heard they had been killed. Throats slit. I heard the words distinctly. I was crouching behind the electric heater between the hallway and the kitchen. I think the grown-ups knew I was there, but they pretended not to see me and I pretended not to listen. They all became super kind to one another again, and I forgot all that. Mama was going into the bathroom more often and coming out with her eyes puffy. Papa hadn’t called for a while. At that point my cousin and I began praying to God. We’d kneel in front of the sofa and pray so everybody could hear us, for everything we could possibly think of. For peace, for the Croatian guard fighters, for Petrinje, for Caesar and Cleopatra, and then we’d get all silly and giggly, but so no one could see. The grown-ups praised us for it and I told everybody I’d grow up to be a nun. We even pretended we were holding Mass and during one of our Masses the postman came to the door. He’d brought a letter from my father. Papa wrote he was well and wasn’t hurt, he really missed us, we’d be seeing each other soon. The grown-ups thought this was a good sign and if anybody was going to save them from this hell it would be us kids. We were proud. A few days later I started noticing Luka and he was my first crush, he was a grade ahead of me. I gave up on being a nun but I still prayed to God for a long time.

I came back from school in the afternoon. Mama was sitting in the dark, curled up on a kitchen chair. On the evening news they weren’t saying a word but after the weather report they played the sad song “Moja Ružo.” She knew the day had come, the Slovenes had announced the news over teletext, but our TV stations were saying nothing, they probably didn’t know what to say. It’s all over, whoever broke through is out, what will happen to the rest God only knows. My aunt came over and hugged Mama, she told her it’s not true, they’re lying, the Slovenes are as bad as the Serbs. Vukovar has fallen and this is bugging me because I’m not sure what it means exactly, and I feel stupid asking. Mama sends me to bed but they stay up for a long time. Early in the morning the phone wakes us. “I’m alive, I’m fine, see you soon.” That’s all. Not where he’s calling from, not when we’ll see him, only that. We dance around the bed, hug each other, kiss.

My brother and I didn’t go to school that day. We got everything ready and with Mama we went into town. With the money we had left we bought meat and all kinds of cakes. Mama and my aunt cleaned the house all afternoon, and in the evening we began to wait. I read the coffee grounds from a few cups of coffee and ran to the window whenever I heard a car. Midnight passed, but no one was sending us to bed. We guessed he was in Vinkovci, there must be crowds and chaos, and maybe they had to be inspected, organized, transportation found, whatever. After a while the three of us went upstairs and Mama placed a candle in the window and stayed up. The next day we went to school. With me in class was Lidija, her dad had broken through the day before. She told me mine was probably a prisoner now and I asked the teacher to let me sit somewhere else.

Under the Christmas tree I got the jeans with knee patches I’d wanted most. My brother got a notebook with a Croatian flag and a cloth backpack for school. It was super cool and I think he liked it because he’d been carrying his books in our aunt’s old briefcase. I wanted to give Mama something but I didn’t have any pocket money. I came up with the idea of slipping a pack of cigarettes out of her carton of Benstons and wrapping it in colored paper along with a pack of Animal Kingdom chewing gum. My cousin got outfits for her Barbie and all of us were pretty happy with the gifts. There was lots of snow that winter and we went sledding. Soon it was time to start the second term, and I was still going to the same school, though I was certain I’d be back in Vukovar before the end of the school year. One evening my uncle came home and told my mother there was an empty apartment in New Zagreb. All we had to do was break in. He had a relative who’d jimmy the lock. Then they’d leave and Mama could wait for the police. No one would send a woman with two kids out into the street from an empty apartment, and if they did throw us out, at least they’d find us another place to stay. That was the most he and my aunt could do for us right now. Željka and her mother also left where they’d been staying with relatives and were put up at an army barracks in Pula by the sea. We talked once over the phone and cried.

I’d never been on the fifteenth floor of a building before. The night before we moved into the apartment, I went out to Samobor to stay there for the night with Granny and her brother. Granny had escaped, after all, through Novi Sad and Hungary, it was only Grandpa whose throat was slit. For a time she stayed in a cellar with her neighbor Marica whom the Serbs had raped and shot in the eye. Nothing happened to Granny. The two of them lived on raw eggs and brandy. Then, somehow, Granny got away and later Marica did, too. She kept talking about it and she was telling everyone her son had probably been killed. No one wanted to hear that. In their house, on the hall table by the phone, there was this

photograph of my father, brother, uncle, and Grandpa, and when they broke into the house, one of the Serbs picked up the picture and said he’d hunt them all down. Granny brought me from Samobor to the apartment and moved right in with us. My mother let us into the high-rise. She was tired and smiling. The apartment had two bedrooms, and the last person to stay there had been a Serbian woman from Derventa. She’d been subletting and we hadn’t known about her because the apartment was being rented off the books. The woman was gone, but she gave my mother gray hair because she left an egg in the fridge, and when Mama entered the apartment the first thing she did was open the refrigerator. She was nearly scared to death that somebody was living there after all. The owner had been given the apartment by his job but he was scared of heights so he’d never lived there. He took us to court anyway to have us evicted. In the lawsuit he said he and his family had gone off on a trip over Christmas and when they came back they’d found us squatting. He said there was a danger of theft of personal belongings and damage to furniture. At court we were represented for free by a famous lawyer and in the papers there was even an article, “Law Written by Tears,” about us. I read it so many times I knew it by heart.

The eviction notice recently served on a Vukovar family squatting in an apartment in a New Zagreb high-rise will be read by many as disrespect for the law. Finally, they’ll say, after all these months while we’ve shrugged, helpless, watching daily break-ins justified by military uniforms, time as prisoners of war, or refugee status . . . But before we went to visit the Vukovar family we discovered that respecting the law differs from case to case. All the fates of these newest squatters are not the same. This story about how they moved in isn’t so different from the others—it started when word got out of an empty apartment and three brave souls jimmied the lock, and it ended with the arrival of the police. This well-oiled routine ended this time, however, with an eviction notice and a summons to court in record time. And something else unusual in the case of this Vukovar family—the total negligence shown by the leaseholder who, as the neighbors and the folk from Vukovar tell us, never even appeared at the door to his place. He was in the building, apparently, but didn’t stop in to visit his new tenants.

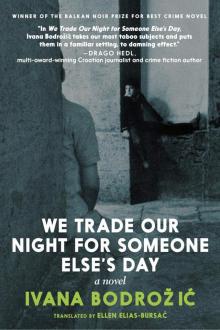

We Trade Our Night for Someone Else's Day

We Trade Our Night for Someone Else's Day The Hotel Tito

The Hotel Tito